[ENDOSTORY #3] UEMR for JNET 2B lesion – A simple technique conquering a difficult case: Is “advanced” always “skillful”?

This week’s ENDOSTORY features a 43-year-old female patient admitted for abdominal pain. Previously, the patient was in good health with no significant medical history. Through clinical examinations, CT scans, abdominal ultrasound, blood count, and blood biochemistry—all results were normal. However, colonoscopy revealed a noteworthy lesion that raised a difficult question: how to select the optimal, safe, and effective method to manage the lesion?

Lesion Assessment: WLI, M-NBI and JNET Classification

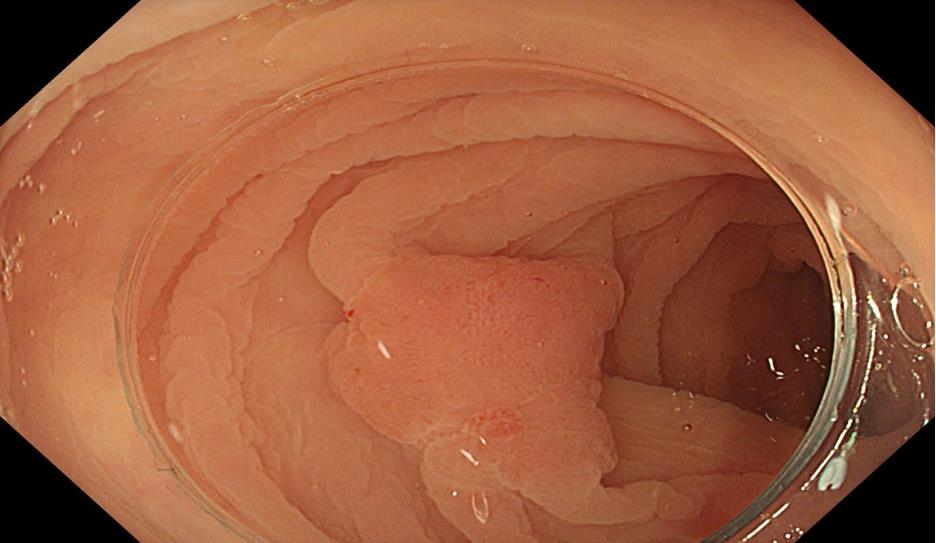

White-light imaging (WLI) detected an LST-NG-F type lesion in the sigmoid colon, approximately 15 mm in size.

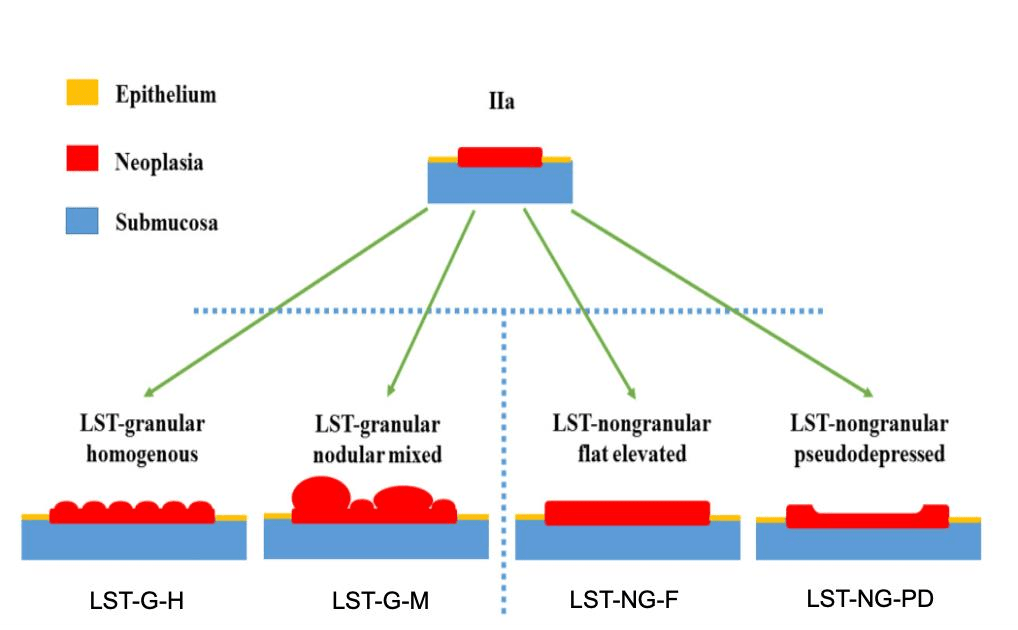

LST (laterally spreading tumors) are neoplastic lesions that spread laterally along the colorectal wall and are ≥10 mm in size. LSTs are classified into two main types:

- LST-G (Granular type): granular, either homogeneous or nodular mixed.

- LST-NG (Non-granular type): non-granular, including flat and pseudodepressed types.

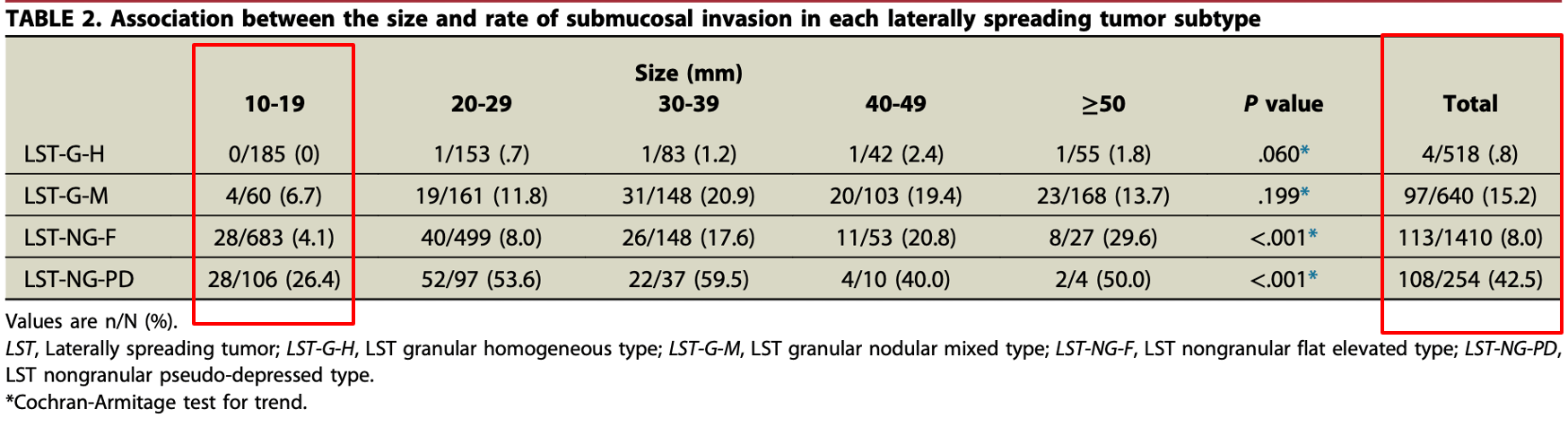

A study by Ishigaki et al. (1) conducted on 2,822 patients with LSTs in the colorectum showed:

- LST-NG-F lesions were the most common.

- Among lesions 10–19 mm in size, the rate of submucosal (SM) invasion was 4.1%.

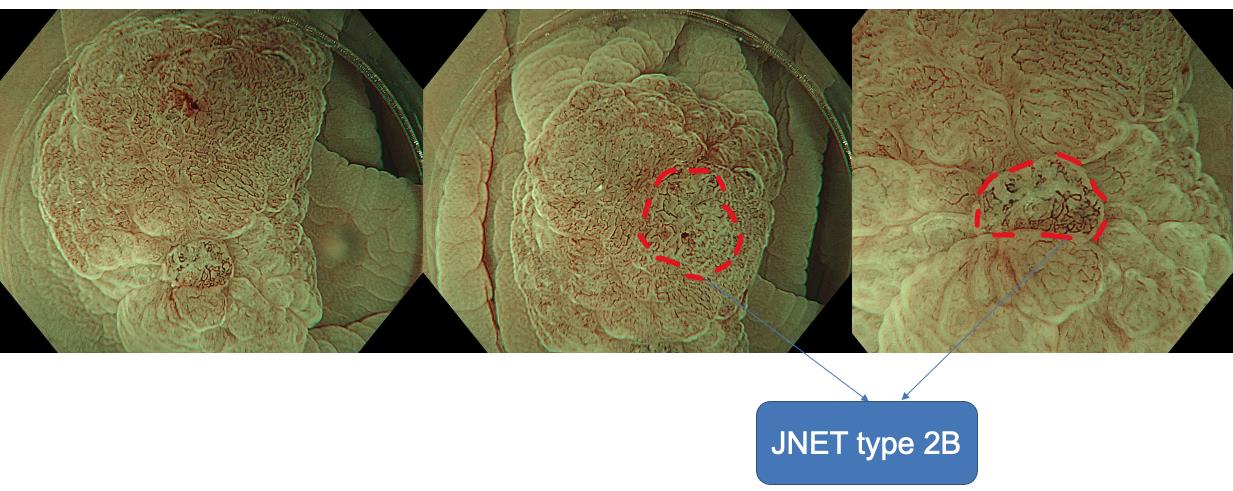

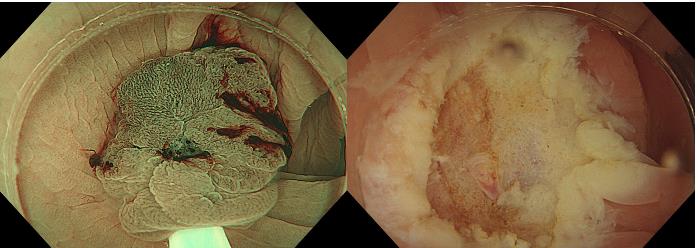

Magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (M-NBI) was performed, and JNET classification was used to predict lesion characteristics and invasion depth. M-NBI showed that most of the lesion area was JNET type 2A; however, two small regions were classified as JNET type 2B.

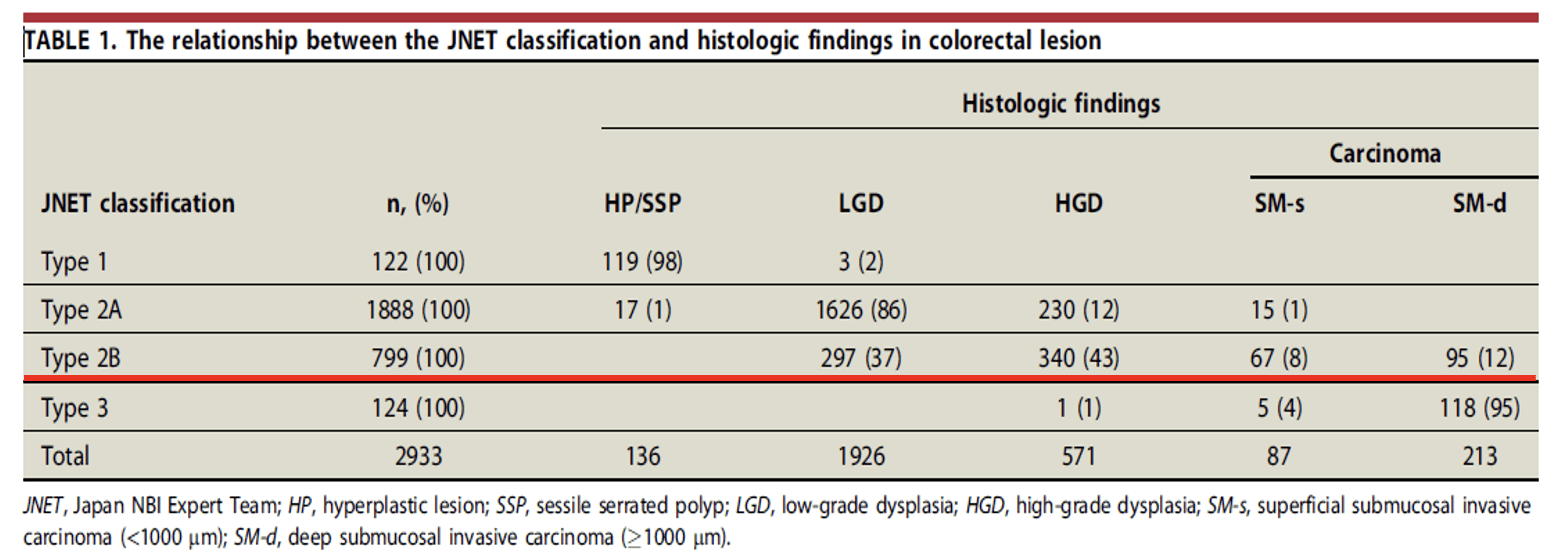

With JNET type 2B, lesions may be high-grade dysplasia and may also indicate deep invasive cancer (2). Therefore, en bloc resection is crucial for curative treatment (R0) and assessing invasion depth.

Diagnosis

Based on endoscopic findings, the lesion was suspected to be high-grade dysplasia or early-stage cancer (T1a), thus requiring en bloc resection with negative margins. Additionally, since the lesion was in the sigmoid colon—where endoscope maneuvering can be challenging due to looping—and was <2 cm in size, the question was whether EMR could be used instead of ESD to achieve en bloc resection with a shorter procedure time and lower cost.

Technique Selection: Standard EMR or Underwater EMR?

Snare-based techniques for colorectal lesion removal have been used since the 1970s. They evolved into CEMR (Conventional Endoscopic Mucosal Resection), involving submucosal injection and marking a new era in non-pedunculated polyp treatment.

Later, in the early 1990s, the emergence of Cold Snare Polypectomy (CSP) marked the “Cold Revolution,” enabling effective resection without electrocautery.

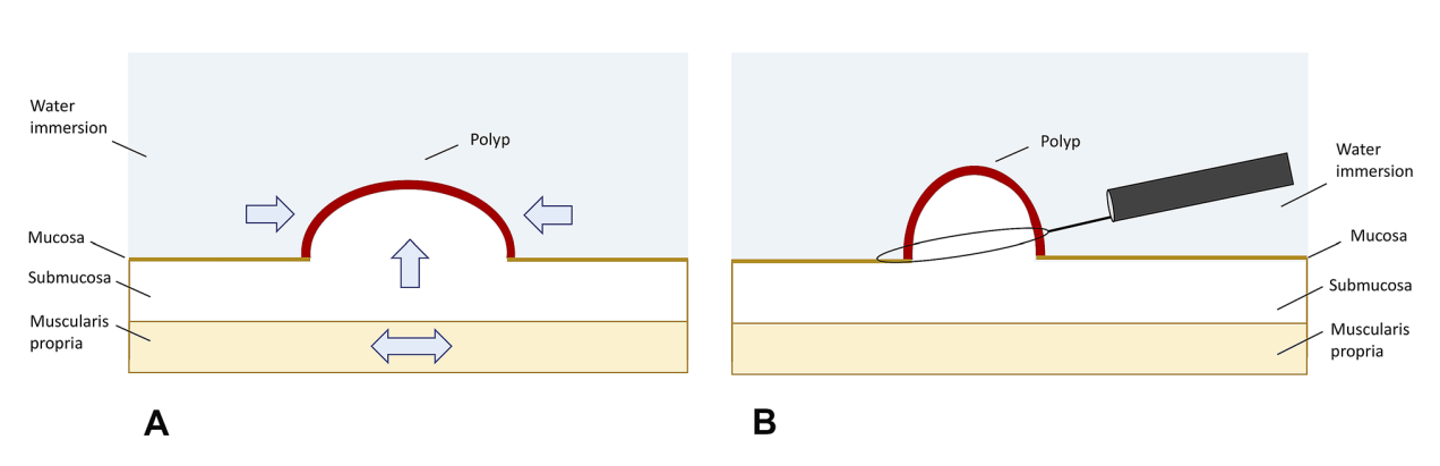

By 2012, EMR further evolved with the introduction of UEMR (Underwater EMR). Instead of submucosal injection, UEMR utilizes a water-filled colon environment for better visualization and manipulation, creating a new approach to endoscopic lesion resection.

UEMR can be quickly implemented in four standard steps:

- Suction out gas from the colon lumen.

- Fill the colon lumen with water.

- Mark the lesion boundary with APC (0.8 flow, 30 W).

- Place the snare outside the APC dots and resect.

So in patient H’s case: LST-NG-F lesion, 15 mm — should we choose CEMR or UEMR?

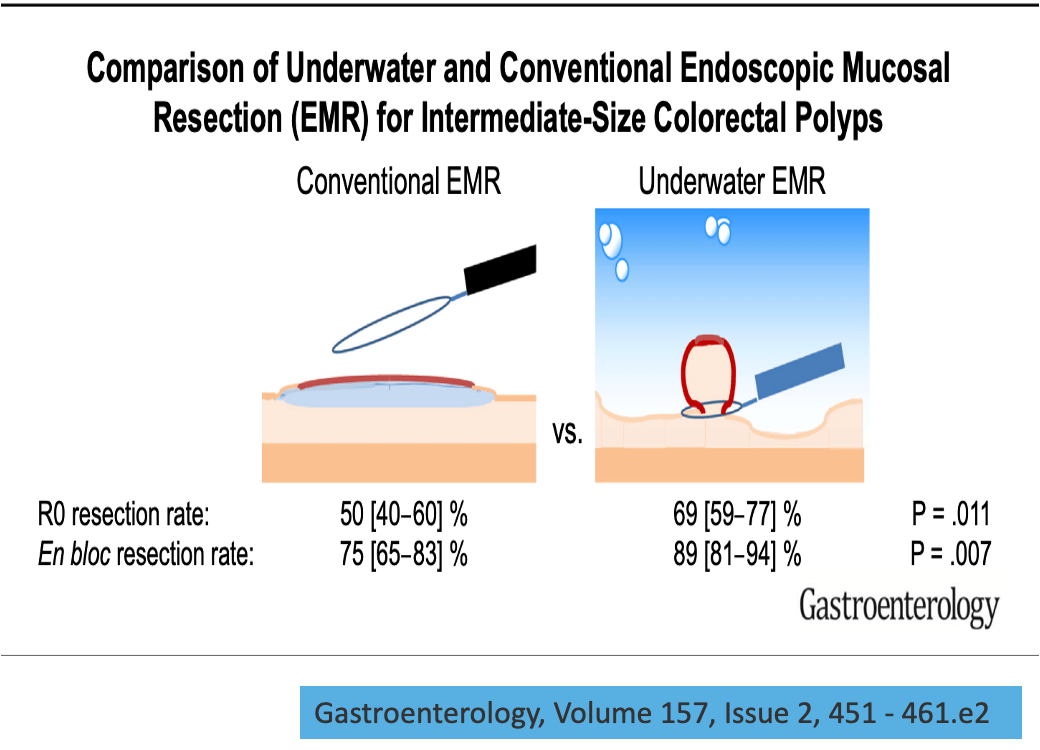

Takeuchi’s study on UEMR showed that for 10–19 mm lesions, UEMR outperformed CEMR in:

- Complete resection rate (CRR)

- En bloc resection rate (EBR)

- Shorter procedure time

- Lower post-procedure complications

In practice, flat, horizontally spreading, non-pedunculated lesions like this one often resist effective submucosal lifting and risk incomplete resection due to snare slippage during CEMR.

In this case, the doctor opted for UEMR. The procedure was completed in 5 minutes. The lesion was resected en bloc without the need for submucosal injection.

Histopathological Results:

- Histological diagnosis: carcinoma in situ (pTis)

- Lateral margin (HM): negative (HM0)

- Vertical margin (VM): negative (VM0)

- No vascular invasion (v0)

- No lymphatic invasion (Ly0)

UEMR – Is It Truly an “Underwater Revolution”?

Takeuchi’s research assessed the effectiveness of UEMR across various colorectal lesion groups: small polyps (<10 mm), medium polyps (10–19 mm), large polyps (≥20 mm), recurrent lesions post-endoscopy, rectal neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), and other special cases.

- Polyps <10 mm: UEMR showed comparable en bloc and complete resection rates to CEMR, shorter procedure time, fewer bleeding complications, and cost-saving by avoiding injection needles.

- Medium polyps (10–19 mm): UEMR offered better or equal en bloc and complete resection rates than CEMR, shorter procedure times, and no increase in complications.

- Large polyps (≥20 mm): UEMR had lower en bloc and complete resection rates than ESD, but shorter procedure times, fewer complications, and some studies showed lower recurrence than CEMR.

- Recurrent lesions post-endoscopy: Compared to CEMR, UEMR had higher complete and en bloc resection rates and lower local recurrence. Compared to ESD (in lesions ~10 mm), UEMR had lower resection rates but significantly shorter procedure and hospitalization times, no complications, and no observed recurrence.

- Rectal NETs: UEMR achieved resection rates comparable to ESD with shorter procedures and fewer complications.

- Special indications for UEMR:

– Lesions in deep indentations like the appendiceal orifice or diverticulum benefit from UEMR’s “floating effect.”

– Lesions in narrow, slippery areas like the lower rectum and anal canal, where submucosal injection would further restrict the space.

– Fibrotic lesions with scarring, e.g., ulcerative colitis-associated lesions.

UEMR Safety Profile:

- Intraprocedural bleeding rate: ~5.2% (95% CI: 4.0%–6.6%), actual range 0%–14.5%, all controlled endoscopically.

- Post-procedural bleeding rate: ~1.4% (95% CI: 0.9%–2.0%), comparable to CEMR.

- Post-polypectomy coagulation syndrome rate: ~0.7% (95% CI: 0.2%–1.5%)

- Perforation rate: ~0.3% (95% CI: 0.1%–0.6%)

Conclusion

- UEMR may be considered for small suspected high-grade dysplasia polyps (<10 mm), medium polyps (10–19 mm), recurrent lesions, and rectal NETs (<15 mm).

- For larger lesions (≥20 mm), further studies are needed to evaluate UEMR’s efficacy compared to ESD.

- UEMR’s complication rates are similar to or lower than CEMR but still require caution in clinical practice.

Lessons from the Case

In interventional medicine—especially with gastrointestinal tumors—no single technique is universally optimal. EMR, UEMR, and ESD each have their own indications and yield the best outcomes when applied appropriately.

Technique selection should not be based on “advancement” or complexity but on a sound understanding of the lesion: location, size, invasion risk, fibrosis, bleeding risk, and patient condition. A simple technique well-suited to the context can deliver excellent outcomes, whereas a complex method applied inappropriately may lead to unnecessary complications. The right intervention is the one best matched to the clinical scenario, maximizing both health and cost-efficiency for the patient.

References:

(1) Ishigaki T et al. Treatment policy for colonic laterally spreading tumors based on each clinicopathologic feature of 4 subtypes: actual status of pseudo-depressed type. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020 Nov;92(5):1083–1094.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.04.033.

(2) Sumimoto et al. (2017). The diagnostic performance of JNET classification for differentiation among noninvasive, superficially invasive, and deeply invasive colorectal neoplasia. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 86. 10.1016/j.gie.2017.02.018.

(3) Takeuchi Y et al. Underwater endoscopic mucosal resection for colorectal lesions: Can it be an “Underwater” revolution? DEN Open. 2022 Jan 9;2(1):e84. doi: 10.1002/deo2.84.

About the ENDOSTORY Series

ENDOSTORY is a series of practical gastrointestinal endoscopy case studies by Lenus Vietnam, aiming to provide useful information for endoscopists. Each week, a selected “story” is posted on the Lenus Vietnam Facebook page at 8:00 PM every Friday.

The series is medically advised by Dr. Trần Đức Cảnh, a specialist in early cancer diagnosis and treatment. Not only has Dr. Trần Đức Cảnh directly participated in numerous complex ESD cases, but he also trains many young endoscopists in Vietnam, contributing to the wide dissemination of this “golden key” technique in early gastrointestinal cancer treatment. His spirit of sharing and spreading knowledge was one of the inspirations behind the ENDOSTORY series.

The program is still in its early stages and welcomes all feedback for improvement. Please send comments or suggestions via inbox to Lenus Vietnam’s fanpage or by email to [email protected] so we can hear your voice.